சிந்து சரஸ்வதி நதி நாகரிகம் ஆரம்பம் பொமு 7500, அதாவது இன்றைக்கு 8500 வருடம் முன்பு என பிர்ரானா என ஹரியானாவின் குருக்ஷேத்திரம் அருகில் உள்ள இடத்தில் கிடைத்த தொல்பொருட்கள் விஞ்ஞான ஆய்வுகள் நிருபித்து உள்ளது.

கோரக்பூர் ஐஐடி நில அமைப்பியல், புவி இயற்பியல் துறை தலைவர் அனிந்தியா சர்க்கார் தலைமையிலான குழு மற்றும் இந்திய தொல்லியல் துறை அதிகாரிகளும் இணைந்து புதிய ஆய்வை மேற்கொண்டனர். இது தொடர்பான கட்டுரை நேச்சர் என்ற பத்திரிகையில் வெளிவந்துள்ளது. அதில் கூறப்பட்டுள்ளதாவது:

அகழ்வாராய்ச்சியின்பேது, மண்பாண்டங்களின் பாகங் கள் கிடைத்தன. இவற்றின் வயதை கண்டறிய நவீன தொழில் நுட்பத்தை பயன்படுத்தினோம். இதில் இவை 6000 ஆண்டு களுக்கு முந்தயை ஹரப்பா நாகரீகத்தை விட தொன்மை யானது என்பது தெரியவந்தது. எனவே சிந்து சமவெளி நாகரீகம் 8,000 ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முந்தையது என்ற முடிவுக்கு வந்துள்ளோம்.

இந்த நாகரீகம் கிறிஸ்து பிறப்பதற்கு முன்பான 7,000-3000 ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முந்தை எகிப்து நாகரீகம், 6,500-3,100 ஆண்டுகளுக்கு முந்திய மெசபட்டோமியா நாகரீகத்துக்கும் முந்தையது. சிந்து சமவெளி நாகரீகம் இதற்கு முன்பே வேரூன்ற தொடங்கி விட்டது. இந்த நாகரீகம் அரியானாவில் பிர்ரானா, ராஹிகார்ஹி போன்ற இடங்களுக்கும் பரவியது. இந்த இடங்களில் அகழ்வாய்வை மேற்கொண்டோம். இங்கு அதிக எண்ணிக்கையிலான பசு,

ஆடு, மான், கலைமான் போன்ற விலங்குகளின் எலும்புகள், பற்கள், கொம்புகள் கிடைத்தன. இவற்றை, கார்பன் 14 டேட்டிங் பகுப்பாய்வு முறையில் சோதனை செய்தோம். இதன் மூலன் இவற்றின் வயது, அப்போதிருந்த பருவ நிலையை தெரிந்து கொள்ள உதவியது. சிந்து சமவெளி நாகரீகம் இந்தியா முழுவதும் பரவியிருந்தது. குறிப்பாக இப்போது மறைந்துவிட்ட சரஸ்வதி நதி அல்லது காஹர்-ஹக்ரா நதியின் கரையோர பகுதிகளில் இது நிறைந்து காணப்பட்டது.

ஆனால் இவை குறித்து நமக்கு தெரியாமலேயே போய்விட்டது. நாம் ஆங் கிலேயர்களின் தொல்லியல் முடிவு களைதான் பின்பற்றி வந்தோம். எங்களது அகழ்வாய்வின் போது, சிந்து சமவெளி நாகரீகத்துக்கு முந்தைய (அதாவது 9000-8000 ஆண்டு களுக்கு முன்பு) முதல் ஹரப்பா நாகரீகம் தொடங்கிய காலம் வரை (8000-7000 ஆண்டுகள்) நன்கு வளர்ந்த ஹரப்பா நாகரீகம் காலம் வரையிலான பாது காக்கப்பட்ட அனைத்து கலாசார நிலைகளையும் கண்டோம்.

ஹரப்பா காலத்தில் திட்டமிடப்பட்ட நகரங்கள், கை வினைப் பொருள்கள் போன்றவை இடம் பெற்றிருந்தன. அரேபியா, மெசபட்டோமியா நகரங்களுடன் வர்த்தகம் செய்து வந்துள்ளனர்.

மெஹெர்கர், இன்றைய பாகிஸ்தானிலுள்ள, பண்டைக்காலக் குடியேற்றப் பகுதி ஆகும். இப்பிரதே சத்தின் புதிய கற்காலக் குடியேற்றங்கள் பற்றிய தொல் லியல் ஆய்வுகளுக்கு மிக முக்கியமான களங்களில் இதுவும் ஒன்று. இக்குடியேற்றத்தின் எச்சங்கள் பாகிஸ் தானின் பலூச்சிஸ்தான் பகுதியில் காணப்படுகின்றன. இது போலன் கணவாய்க்கு அருகிலுள்ள கச்சிச் சமவெளிப் பகுதியில், சிந்துநதிப் பள்ளத்தாக்குக்கு மேற்கே, குவேட்டா (Quetta),, காலத் Kalat)), சிபி (Sibi) ஆகிய நகரங்களுக்கு இடையே அமைந்துள்ளது.

பிரான்சைச் சேர்ந்த தொல்லியலாளர்களால் கண்டுபிடிக்கப்பட்ட இக் களம், உலகின் பழமையான மனித குடியேற்றங்களில் ஒன்றாகக் கருதப்படுகின்றது. இதன் ஆதிக் குடியேற்ற வாசிகள், பலூச்சிக் குகை வாழ்நரும், மீனவர்களும் ஆவர். 1974 இல் நடத்தப் பட்ட தொல்லியல் ஆய்வுகளை (ஜர்ரிகேயும் (Jarrige) மற்றவர்களும்) அடிப்படையாகக் கொண்டு, இப் பகுதியே தென்னாசியாவின் அறியப்பட்ட வேளாண் மைக் குடியேற்றங்களில் முற்பட்டதாகக் கருதப்படு கின்றது. இங்குள்ள குடியேற்றத்துக்கான மிக முற்பட்ட தடயங்கள் கி.மு. 7000 அய்ச் சேர்ந்தவை. தென்னாசி யாவின் முற்பட்ட மட்பாண்டச் சான்றுகளும் இங்கேயே கிடைத்துள்ளன.

இந்த நகரங்கள், குடியேற்றங்களுடைய ஒரு தன்மைத்தான அமைப்பு இவையனைத்தும் ஒரு உயர் வளர்ச்சி நிலையில் சமூக ஒருங்கிணைப்பு வல்லமை கொண்ட ஒரே நிர்வாகத்திக் கீழ் அமைந்திருந்தமையைக் காட்டுகின்றது.

பொருளடக்கம்

சிந்துவெளிப் பண்பாட்டின் காலப் பகுப்பு[தொகு]

| கால எல்லை | கட்டம் | சகாப்தம் |

| 7000 – 5500 | மெஹெர்கர் I | ஆரம்பகால உணவு உற்பத்தி |

|---|---|---|

| 5500-3300 | மெஹெர்கர் II-VI | மண்டலமயமாக்கல் (Regionalisation Era) |

| 3300-2600 | முந்திய ஹரப்பா | |

| 3300-2800 | ஹரப்பா 1 (ரவி கட்டம்) | |

| 2800-2600 | ஹரப்பா 2 (கொட் டிஜி கட்டம், நௌஷாரோ I, மெஹெர்கர் VII) | |

| 2600-1900 | முதிர் ஹரப்பா | ஒருங்கிணைப்பு சகாப்தம் (Integration Era) |

| 2600-2450 | ஹரப்பா 3A (நௌஷாரோ II) | |

| 2450-2200 | ஹரப்பா 3B | |

| 2200-1900 | ஹரப்பா 3C | |

| 1900-1300 | பிந்திய ஹரப்பா (கல்லறை எச் கலாச்சாரம்) | ஓரிடமாக்கல் (Localisation Era) |

| 1900-1700 | ஹரப்பா 4 | |

| 1700-1300 | ஹரப்பா 5 |

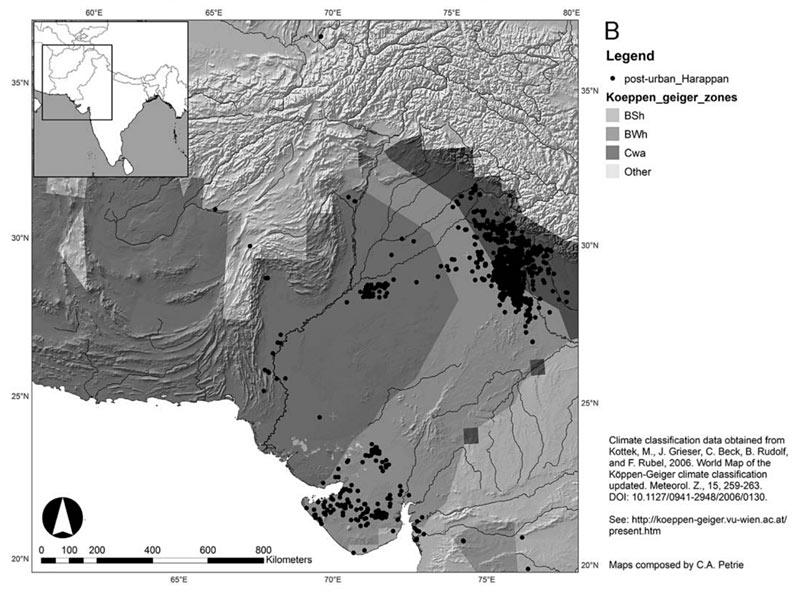

Map of the Indus Valley Civilization

Map of the Indus Valley Civilization Dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro

Dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro Shiva Pashupati

Shiva Pashupati Shiva

Shiva Vishnu Riding Garuda

Vishnu Riding Garuda Agni

Agni Indus Valley

Indus Valley Banner at the North Gate of Dholavira

Banner at the North Gate of Dholavira Ganesha

Ganesha Rajarani Temple, Bhubaneshwar

Rajarani Temple, Bhubaneshwar A Bodhisattva, Gandhara

A Bodhisattva, Gandhara Maruyan Empire

Maruyan Empire Kushan Empire & Neighboring States

Kushan Empire & Neighboring States Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh

Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh Kailasanatha Temple, Kanchipuram

Kailasanatha Temple, Kanchipuram Harappa Ruins

Harappa Ruins Harappan Ceremonial Vessel

Harappan Ceremonial Vessel Well and Bathing Platform, Harappa

Well and Bathing Platform, Harappa

World Map of Herodotus

World Map of Herodotus Map of Alexander the Great's Conquests

Map of Alexander the Great's Conquests The Empire of Alexander the Great

The Empire of Alexander the Great Hellenic Trade Routes, 300 BCE

Hellenic Trade Routes, 300 BCE Indo-Greek Campaigns

Indo-Greek Campaigns Gandhara Buddha

Gandhara Buddha Buddha with Hercules Protector

Buddha with Hercules Protector Yakshi

Yakshi