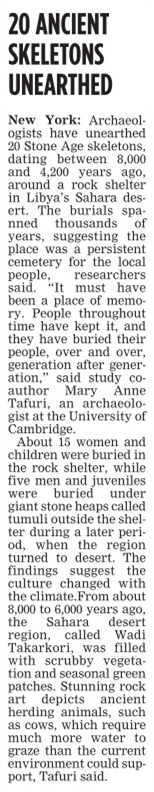

Note: The Tirupparankundram stone inscription, discussed in the following reports, seems to use signs comparable to the signs found on the pottery of Bet Dwarka dated to ca. 1528 BCE.

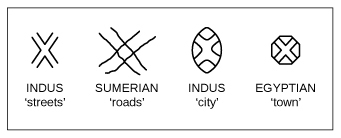

The following report seeks to compare the writing with some Sangam age Chera and Pandya coins which include an elephant glyph. Elephant glyph occurs on Indus script, pointing to an apparent continuity of the Indus writing system in many parts of India. It is not uncommon to find many early punch-marked coins and cast coins all over India containing glyphs such as svastika, tree-on-railing, elephant, tiger, crocodile-holding-fish-in-jaw, mountain-passes, ficus leaf, standard device (brazier? gimlet?) -- all glyphs seen as Indus writing legacy.

Kalyanaraman

Published: February 17, 2013 02:40 IST | Updated: February 17, 2013 02:40 IST

‘Trisula found on Tirupparankundram inscription is a Saivite symbol’

Special Correspondent

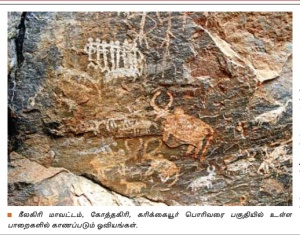

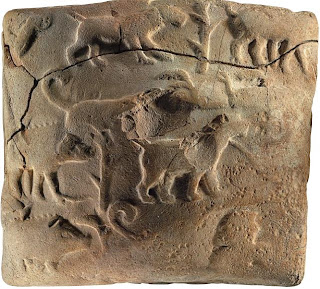

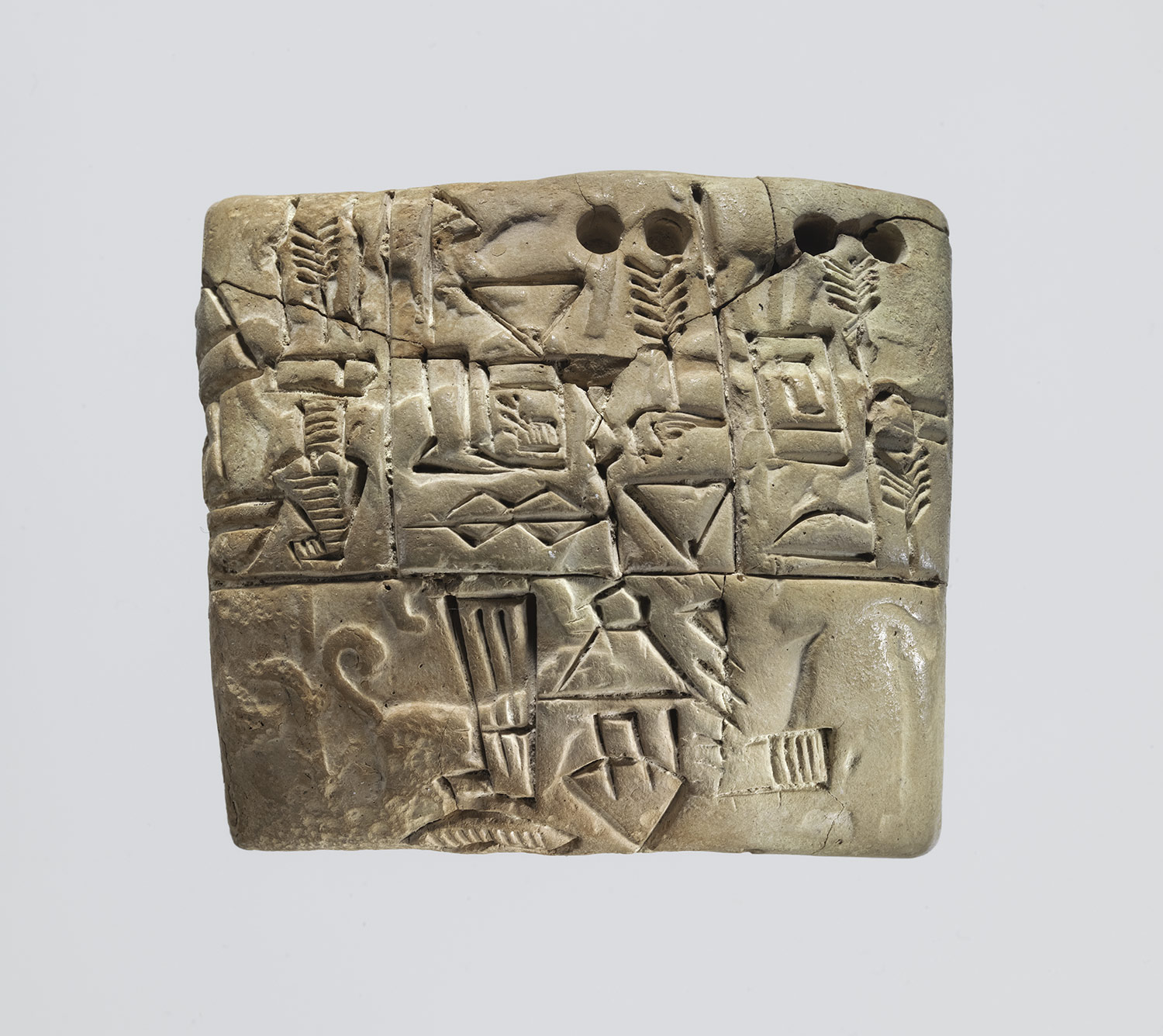

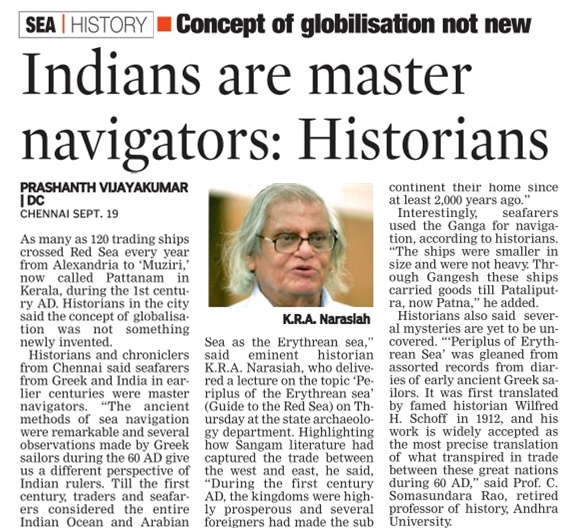

The trisula symbol, engraved before a standing elephant, on the Sangam age Pandya and Chera coins. Photo: R. Krishnamurthy

It is difficult to accept Jaina connection, says Krishnamurthy

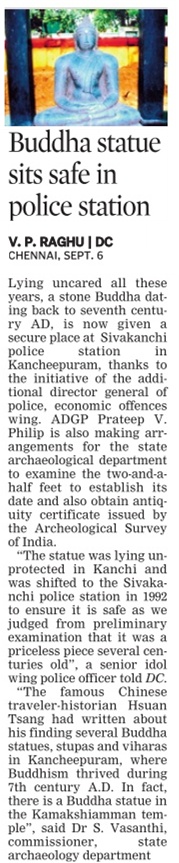

The trisula symbol at the end of the first line of the Tamil-Brahmi inscription, which was found on the Tirupparankundram hill near Madurai, is a Saivite symbol, argues R. Krishnamurthy, Editor, Dinamalar, a Tamil daily.

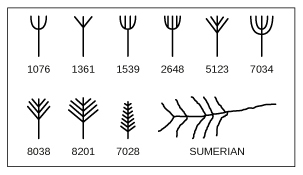

The trisula symbol can be seen in a rectangular or square type of the Tamil Sangam age Pandya copper coins and the Sangam age Chera coins, says Dr. Krishnamurthy, a reputed numismatist with a knowledge of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions.

“In view of the fact that we find the trisula symbol in the inscription,” he argues, “it will be extremely difficult to accept the Jaina connection” as argued in the story, ‘Tamil-Brahmi script discovered on Tirupparankundram hill,’ which appeared in The Hindu, dated February 14, 2013.

The inscription, discovered on January 20 this year, has two lines: Muu-na-ka-ra and Muu-ca-ka-ti.Quoting specialists in Tamil-Brahmi, the article said the inscription could refer to an elderly Jaina monk who attained salvation by fasting unto death.In the first line of the script, the second letter ‘na’ and the third letter ‘ra’ may have been inscribed in the Bhattiprolu script, Dr. Krishnamurthy says.

“We can read the legend as ‘mu-nakar,’ an ancient town. The Bhattiprolu script has been used in the Sangam age Pandya ‘Peruvaluthi’ coin. The word ‘Sakti’ in the second line refers to Goddess Meenakshi. This inscription may belong to circa second century BCE,” he argues.

http://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/history-and-culture/trisula-found-on-tirupparankundram-inscription-is-a-saivite-symbol/article4422864.ece

Published: February 14, 2013 00:30 IST | Updated: February 14, 2013 03:58 IST

Tamil-Brahmi script discovered on Tirupparankundram hill

T. S. Subramanian

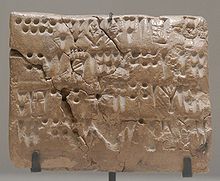

The picture shows the estampage on the Tamil- Brahmi script discovered on January 20, 2013 on a step leading to a pond on top of the Tirupparankundram hill, near Madurai. Photo: R. Ramesh

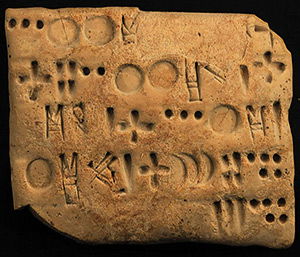

The picture shows the estampage on the Tamil- Brahmi script discovered on January 20, 2013 on a step leading to a pond on top of the Tirupparankundram hill, near Madurai. Photo: R. Ramesh Handwritten copy of the Tamil-Brahmi script discovered on January 20, 2013 on top of the Tirupparankundram hill, near Madurai. The script, in two lines, reads “Muu-na-ka-ra” and “Muu-caka- ti.” The script is datable prior to the first century BCE. Photo: M. Prasanna

Handwritten copy of the Tamil-Brahmi script discovered on January 20, 2013 on top of the Tirupparankundram hill, near Madurai. The script, in two lines, reads “Muu-na-ka-ra” and “Muu-caka- ti.” The script is datable prior to the first century BCE. Photo: M. PrasannaThe lines read as “Muu-na-ka-ra” and “Muu-ca-ka-ti”

Young archaeologists M. Prasanna and R. Ramesh like to climb the hills around Madurai, which have pre-historic rock art, Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions on the brow of natural caverns, beautiful bas-reliefs of Jaina “tirthankaras” and beds cut on the flat rock surface for the Jaina monks to sleep on. These hills include Mankulam, Keezhavalavu, Tiruvadavur, Varichiyur, Mettupatti, Anaimalai, Kongar Puliyankulam and Muthupatti.

The duo aspired to discover a Tamil-Brahmi script on the hills. While Prasanna is an assistant archaeologist in the Archaeological Survey of India, Ramesh works in the University Grants Commission-Special Assistance Programme under Professor K. Rajan of the Department of History, Pondicherry University.

On January 20, 2013, they climbed the Tirupparankundram hill, where three Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions, datable to the first century BCE, were discovered many decades ago. As they climbed the several hundred steps leading to the Kasi Viswanathar temple, they wondered whether they would be lucky this time. Behind this temple are bas-reliefs of Jaina tirthankaras on the rock surface. There are also recently carved images of Ganesa, Muruga, Bhairava and others. Near the temple, there is a pond and a shrine dedicated to Machchamuni (matsya muni), meaning fish god. The pond is full of fish. There are steps cut on the rock, leading to the pond.

As they were scanning the rock surface, their eyes fell on the steps leading to the pond and they saw what looked like a Tamil-Brahmi script in two lines. Excited, they turned the pages of the book titled “Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions,” published by the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department in 2006. They read the pages on the earlier discoveries of the Tamil-Brahmi script at Tirupparankundram and found that this was a new discovery. They rang up Dr. Rajan who confirmed that it had not been documented earlier.

The lines, each having four letters, read as, “Muu-na-ka-ra” and “Muu-ca-ka-ti.” The first line has a trishul-like symbol as a graffiti mark at its end. The first letter “muu” can mean “three” or being ancient or old. “In the present context, the meaning of ancient is more probable,” Ramesh and Prasanna said. The na-ka-ra/na-kar-r represents a town or city. So the first line could be read as “ancient town,” probably meaning Madurai, they suggested. In the second line, the first letter “muu” again stands for “ancient or old.” The remaining three letters, ca-ka-ti/ca-k-ti may represent a “yakshi,” they said. (Yakshis are women attendants of the 24 Jaina tirthankaras). “So the inscription can be read as goddess of the ancient city. But it is open to different interpretations,” they said.

V. Vedachalam, retired senior epigraphist, Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department, said the first line stood for an elderly Jaina monk and the second one could mean “motcha/moksha gadhi.” So the script could stand for a Jaina monk who, facing north, went on a fast unto death there. That is, he attained nirvana. This is the first time that a Tamil-Brahmi script, referring to a Jaina monk who fasted unto death, had been discovered. Other Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions referred to donors who cut beds on rocks for Jaina monks or sculpted rock-shelters for them.

A. Karthikeyan, Professor, Department of Tamil Studies in Tamil University at Thanjavur, suggested that the inscription could be read as “the attainment of liberation or salvation (moksha) of a female monk (saadhvi), namely elderly naakaraa. “Moksha gadhi” could be changed into muccakati. “It is difficult to assign a date to this inscription but it can be dated prior to the first century BCE,” said Dr. Rajan.

http://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/history-and-culture/tamilbrahmi-script-discovered-on-tirupparankundram-hill/article4412125.ece