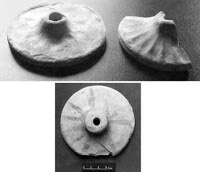

On November 15th an article has been published on Nature Communications about a copper amulet (see the photo above) from Mehrgarh, Baluchistan, presented as the earliest object produced through the lost-wax technique.

At the same time, the amulet appears as the earliest reproduction of a spoked wheel. Of course, it is only a shape, but is it possible to use the shape of a wheel before it exists? Or was the symbol itself that finally brought to the creation of the spoked wheel, like a Platonic idea taking shape through a demiurge? It can be an intriguing debate between a materialistic and idealistic approach to history and culture... but let's analyze the issue.

First of all, about the context: "The wheel-shaped amulet inventory number MR.85.03.00.01 was collected in 1985 at the MR2 site of Mehrgarh during the excavations of the ‘Mission Archéologique de l’Indus’ (dir. Jean-François Jarrige)"

The MR2 site belongs to the Period III of Mehrgarh, associated with the Chalcolithic and dated by the Wikipedia entry and by Kenoyer 4800-3500 BC. More precisely, the paper speaks of "sector X, Early Chalcolithic, end of period III, 4,500–3,600 BC." However, in the supplementary information we read: "Wheel-shaped ornament discovered by Anaick Samzun in 1985 from a surface recollection at the MR2 site. Despite the fact that the copper artefact was not discovered in its primary position, it belongs to the Early Chalcolithic period since the MR2 site dates entirely from this period."

The date given for the object is 6000 years old, but it is clearly a guess, a full number in the middle between 4500 and 3600 BC, which is the dating given here of the site MR2. In the same site also other wheel-shaped objects have been found: one, fragmentary, "close to the skull of a woman buried in the individual tomb H 33". This suggests that such objects were common in Early Chalcolithic Mehrgarh, and had a sort of religious meaning that could be connected also with death.

For a parallel, we can cite the Celtic use of wheel amulets (from here):

Symbolic votive wheels were offered at shrines (such as in Alesia), cast in rivers (such as the Seine), buried in tombs or worn as amulets since the Middle Bronze Age. Such "wheel pendants" from the Bronze Age usually had four spokes, and are commonly identified as solar symbols or "sun cross". Artefacts parallel to the Celtic votive wheels or wheel-pendants are the so-called Zierscheiben in a Germanic context. The identification of the Sun with a wheel, or a chariot, has parallels in Germanic, Greek and Vedic mythology.

On the other hand, how old are the earliest traces of real spoked wheels used for vehicles? A common answer is: Sintashta in the Russian steppe, around or slightly before 2000 BC (for instance in the detailed book of Anthony "The Horse, the Wheel, and Language"). There are graves containing impressions of spoked wheels, evidently made of wood. The same book explains that the earliest depictions of spoked wheels are later in the Near East: on cylinder seals at Kanesh (Kültepe in Turkey), the important Assyrian colony and Hittite city, around 1900 BC. Anthony used these facts to support an origin from the steppes of the chariots with spoked wheels, followed with enthusiasm by the fans of the steppes. I consider this passion for the steppes an enigmatic and irrational propensity, maybe explainable as a sort of revenge and affirmation of superiority by northern and eastern Europeans on Asians and Mediterraneans, usually regarded (with some obvious reasons) as the source of civilization.

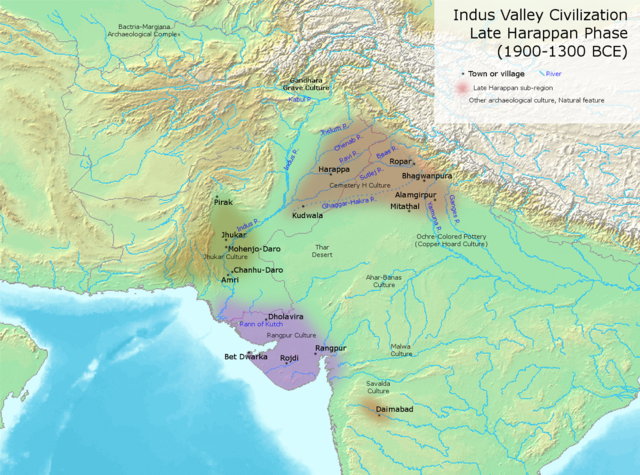

Anyway, there are some facts that are ignored in this picture. Not only the wheel-shaped amulets, already discovered in the '80s and apparently completely neglected in the debate, but also some terracotta wheels from models of carts found in Harappan sites in Western India and in Shahr-i Shokhta, Iran, in levels dated to the 3rd millennium BC, most probably before the Sintashta graves.

|

| Terracotta wheels from Banawali and Rakhigarhi, Mature Harappan period |

|

| Terracotta wheels from Bhirrana, Mature Harappan period |

| Terracotta wheel from Shahr-i Sokhta, 2750-2200 BC |

At Harappa we find evidence for the use of terracotta model carts as early as 3500 BC during the Ravi Phase at Harappa [...] No carts or wheels dating to this early time period have been reported from any sites in Afghanistan or Central Asia, or even from sites such as Mehrgarh and Nausharo that are located at the edge of the Indus plain. [...] it is now possible to say that, on the basis of the currently available archaeological evidence, the development of Indus wheeled carts appears to be the result of indigenous processes occurring out in the alluvium and not the result of diffusion from mountainous regions to the west.

Evidently, he did not consider the wheel-shaped amulets from Mehrgarh, but he was dealing with models of carts and terracotta wheels, which are very different from the copper amulets.

But what is impressive here is that he puts the first wheeled carts in the region in the Indus valley, something completely ignored by this passage from the Wikipedia entry on the wheel:

The first evidence of wheeled vehicles appears in the second half of the 4th millennium BCE, near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia (Sumerian civilization), the Northern Caucasus (Maykop culture) and Central Europe (Cucuteni-Trypillian culture), so the question of which culture originally invented the wheeled vehicle is still unsolved.

Can we consider normal that the Indus valley is not mentioned 12 years after the article of Kenoyer? And is it normal that in the book of Anthony, published in 2007, there is no reference to the same article? Maybe yes, we can consider it normal, because South Asian archaeology is evidently out of the range of mainstream knowledge, even when the authors are important Western archaeologists like Kenoyer. I am the only one who has added references to Indian findings in the paragraph of that entry on the history of the wheel, and fortunately they have not been removed.

Anthony in his book, p.69, states that the Baden culture ceramic wagon models dated 3300-3100 BC are "the oldest well-dated three-dimensional models of wheeled vehicles", and there is no mention of the Harappan findings.

An exception to this silence is the Bulgarian M. Ivanova, who, about the Maykop wheels from northern Caucasus, says in "The Black Sea and the Early Civilizations of Europe, the Near East and Asia", pp.121-2:

The remains of two wooden wheels at Novokorsunskaja allow some suppositions about the type of vehicle to which they belonged. In size, they are similar to wheels of the Catacomb culture [...] The presence of a hub suggests a vehicle with rotating wheels and a fixed axle. The vehicle from which the wheels at Novokorsunskaja originate might have been a two-axle wagon like the roughly contemporary wagon from Koldyri on the Lower Don. But it is also possible that the find from Novokorsunskaja was a two-wheeled cart. Clay models of two-wheeled carts with rotating wheels attest to the use of this type of vehicle in central Asia and the Indus valley in the late fourth millennium BC. At Altyn-depe in south Turkmenistan, such models occur in the second half of the fourth millennium (Namazga III period) and become more common in the early centuries of the third millennium. Cattle figurines with holes in the withers for attaching the yoke have been recovered at Kara-depe. Comparable models appeared in the Indus valley around 3500–3300 BC, during the Ravi-Phase of the Indus culture at Harappa (Kenoyer 2004, 90 f., Fig. 2).

So, going back to Kenoyer's article, the American archaeologist continues speaking of the wheels found from the Early Harappan period (2800-2600 BC), 17 in number; 4 of them from Harappa have painted motifs, and one "shows radiating lines that could represent spokes". The design given in the paper (Figure 4, no.7) can suggest spokes indeed. Kenoyer adds that the technology of wheel transport however is not well attested out of Harappa itself, and he remarks, citing Tosi 1968, that also Shahr-i Sokhta has not given wheels. Probably, the terracotta wheel exposed in the Museum of Oriental Art in Rome shown above has been found later than Tosi's publication. By the way, it is remarkable that there are also zebu (Bos indicus) figurines, and since zebus were domesticated around Mehrgarh, it suggests a significant influence from the East, from the Indian subcontinent. A tendency shown also in the historical period, since the Helmand area (Arachosia) was known as White India and was more Indian than Iranian until the Muslim conquest (see here).

On the other hand, Kenoyer adds (p.8):

However, we have a confirmation that spoked wheels were well known in Mature Harappan India. L.S.Rao, who apparently did not know Kenoyer's article (he cites only a 1998 book of him), remarks that they have not been found in the Indus valley, but we have seen that an example was already in an Early Harappan level of Harappa, and we can add the spoked wheel from Shahr-i Sokhta contemporary with Mature Harappan. Mehrgarh's amulets seem a bit too early, also compared with the earliest cart models from Harappa (3500 BC). However, 3600 BC as the lowest limit of the Chalcolithic level of the amulets is not so far from it, but very far from the first attestations of a terracotta wheel with spokes (after 2800 BC, Early Harappan). Moreover, those copper objects are quite different from the terracotta wheels, and they can also be pure symbols. But why in that shape, and symbols of what? We can remark that they have six spokes. What can be the meaning of that number?If you search for numerical symbolism in ancient India, the best place is the hymn RV I.164. There we read in st.11-12:

dvādaśāraṃ nahi tajjarāya varvarti cakraṃ pari dyāṃ ṛtasya |

ā putrā agne mithunāso atra sapta śatāni viṃśatiśca tasthuḥ ||

pañcapādaṃ pitaraṃ dvādaśākṛtiṃ diva āhuḥ pare ardhe purīṣiṇam |

atheme anya upare vicakṣaṇaṃ saptacakre ṣaḷara āhur arpitam ||

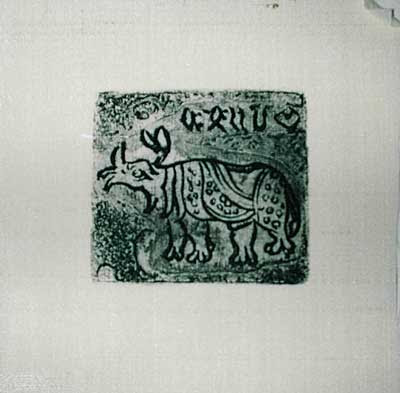

The similarity of shape with Mehrgarh's amulets is remarkable, and the fact that it is placed over the heroic scene on the convex tablet shows its strong symbolic character, probably with a solar meaning as in the Vedic hymn.

Further north in Central Asia, the first carts appear during the subsequent Namazga V period (2600-2200 BC) that corresponds to the Harappa Period in the Indus Valley, and these are four wheeled carts drawn by one or two camels and not by bullocks. Since camels were not domesticated in the Indus valley, we can assume that the use of camel carts is an indigenous process in Central Asia and that the construction of four wheeled carts in Central Asia is also a local phenomenon.About the Mature Harappan period, Kenoyer speaks of a significant increase in the number of terracotta carts and wheel fragments, and has also something to say about the reproduction of spoked wheels:

The most controversial discussion revolves around the construction of spoked wheels that have been associated with the use of the horse drawn chariot and by extension, the Indo-Aryan culture. In India single examples of "spoked wheels" have been reported from the sites of Lothal, Rupar, and Mitathal, Banawali and most recently at Rakhigarhi [...] Perhaps the most convincing example of a spoked wheel comes from the site of Rahkigarhi, presumably from the Harappan levels though the excavation report has not yet been published. In this example there are eleven radiating spokes that would have provided considerable support to a light outer rim.The wheel in question is that of the photo above. Kenoyer does not speak of Bhirrana, that was excavated in the same period of the publication of his article (2003-2006). And in Puratattva no.36, of the year 2005-6, after Kenoyer's article, we find an article by L.S.Rao about wheels found in Bhirrana. There are several instances of wheels with painted spokes or spokes in low relief, already from the Early Mature Harappan period. I suppose the dating of this period should be around 2600 BC (the accepted beginning of the Mature Harappan), although a paper by Sarkar et al. published on Nature gives even 6.5–5 ka BP for this period. Being too far from the consensus on the periodization of the Indus-Saraswati culture, I do not dare to accept it.

However, we have a confirmation that spoked wheels were well known in Mature Harappan India. L.S.Rao, who apparently did not know Kenoyer's article (he cites only a 1998 book of him), remarks that they have not been found in the Indus valley, but we have seen that an example was already in an Early Harappan level of Harappa, and we can add the spoked wheel from Shahr-i Sokhta contemporary with Mature Harappan. Mehrgarh's amulets seem a bit too early, also compared with the earliest cart models from Harappa (3500 BC). However, 3600 BC as the lowest limit of the Chalcolithic level of the amulets is not so far from it, but very far from the first attestations of a terracotta wheel with spokes (after 2800 BC, Early Harappan). Moreover, those copper objects are quite different from the terracotta wheels, and they can also be pure symbols. But why in that shape, and symbols of what? We can remark that they have six spokes. What can be the meaning of that number?

dvādaśāraṃ nahi tajjarāya varvarti cakraṃ pari dyāṃ ṛtasya |

ā putrā agne mithunāso atra sapta śatāni viṃśatiśca tasthuḥ ||

pañcapādaṃ pitaraṃ dvādaśākṛtiṃ diva āhuḥ pare ardhe purīṣiṇam |

atheme anya upare vicakṣaṇaṃ saptacakre ṣaḷara āhur arpitam ||

So translated by Jamison and Brereton (see here):

11. Twelve-spoked, the wheel of truth [=the Sun] ever rolls around heaven—yet not to old age. Upon it, o Agni, stand seven hundred twenty sons in pairs [=the nights and days of the year].

12. They speak of the father [=the Moon] with five feet [=the seasons] and twelve forms [=the months], the overflowing one in the upper half of heaven.

But these others speak of the far-gazing one [=the Sun] in the nearer (half) fixed on (the chariot) with seven wheels [=the Sun, Moon, and visible planets] and six spokes [=the seasons, in a different reckoning].

The word ṣaḷ-ara means 'having six spokes' and it is the Rigvedic equivalent of ṣaḍ-ara, found in a repetition of st.12 placed in AV (Śaunaka recension) 9.9.12 before a repetition of st.11 (see here for the translation). The same stanza 12 is cited in the Atharvavedic Praśna Upaniṣad, commented by Śaṃkara, who recognized the symbolism of the year and seasons. About ṣaḍara, he glossed with the compound ṣaḍ-ṛtu-mat- 'having six seasons'.

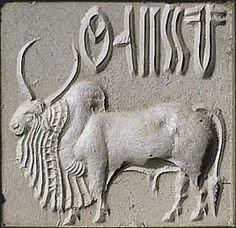

Now, in Harappan seals we find a sort of spoked wheel, regularly with six spokes:

|

| Harappan square seals with the character of the 'spoked wheel' (from this site) |

|

Plano convex molded tablet discovered in Harappa, 1997. From harappa.com |

The similarity of shape with Mehrgarh's amulets is remarkable, and the fact that it is placed over the heroic scene on the convex tablet shows its strong symbolic character, probably with a solar meaning as in the Vedic hymn.

Also in historical times, the wheel of Viṣṇu, called Sudarśana-cakra, is often described as having six spokes, symbolizing again the six seasons (see e.g. here).

Thus, we would have again a striking instance of cultural continuity, this time from Chalcolithic Mehrgarh to historical India through the Harappan age.

Mehrgarh's 'spoked wheel' perhaps was not a real wheel but a circle symbolizing the cyclical time of the year and the Sun, like the Native American 'cross in a circle' or the Sun cross of European prehistory. We can also compare Bactrian bronze seals having circular shape, the last one is directly comparable to the one from Mehrgarh, although with 8 spokes:

However, the Harappan terracotta wheels reproduce real wheels, and the ancient six-spoked symbol could be easily identified with the new technological object, that had also the advantage of representing the idea of movement of the Sun. Now, the spoked wheel has been associated with the Aryans because it is mentioned in the Vedas. In Vedic rituals like the Vājapeya we find a ratha-cakra 'chariot wheel' placed on a post to symbolize the Sun, with 17 spokes. According to the Kātyāyana Śrautasūtra, before climbing the post, the officiant is hailed with formulas, which declare him lord of the 12 months and the 6 seasons of the year (see here).

The wheel was so central in the ancient Indian worldview that the ideal king was called Cakravartin 'a ruler the wheels of whose chariot roll everywhere without obstruction' (Monier-Williams, translating the German Petersburg dictionary). Both in Jain and Buddhist traditions this emperor of the Earth has, among the seven jewels (ratna), the 'jewel of the wheel', symbol of Dharma, in the sense of justice and social order.

|

| Relief with Cakravartin from Amaravatī |

Also Ashoka, the great emperor, used a wheel, evident in the pillar below, with 24 spokes, explained in various ways and adopted in the Indian flag itself. However, it seems that on the top of the lions there was a wheel with 32 spokes, that can be interpreted as the 32 marks of the Mahāpuruṣa (Great Man) proper to the Buddha and the Cakravartin king. Interestingly, in the legend of Ashoka called Aśokāvadāna, the number of pilgrimage sites connected with the life of the Buddha and visited by Ashoka totals thirty-two (see J.S. Strong, The Legend of King Aśoka, Princeton 1983, pp.123-5).

Radha Kumud Mookherjee, an historian and member of the Indian Parliament at the time of Nehru, tried to include that wheel on the national emblem (see here):

Radha Kumud Mookherjee, an historian and member of the Indian Parliament at the time of Nehru, tried to include that wheel on the national emblem (see here):

“It appears that a ‘chakra’ with thirty-two spokes was, in the original, placed atop the shoulders of the four lions. The basic idea was that the wheel of righteousness, representing spiritual forces, should be above the four lions, representing material strength. (However) there is evidence to show that this top wheel fell off the shaft on which it rested and so in the Sarnath Museum one sees the lion capital without the top.”“We feel our state emblem should not embody in itself, as it were, a historical mistake. The sheer accident of the wheel being detached from the pillar should not justify a truncated copy of the original sculpture. Besides, the chakra, which is now only engraved in the abacus, does not convey the significance and symbolism of the original, which stresses the superiority of spiritual values. It will be in conformity with our principles and ideals if we correct the mistake. If we have wanted to revive the Ashokan ideals, as indeed we have done, let us not perpetuate a mutilated variant of this monument.”

Pragyan Kumud, a descendant of the historian, has decided to "go up to the highest authorities until the change is made", explaining: “There is something in symbolism, otherwise we would not need national emblems. Maybe, if the chakra of peace was put back into its rightful place, our country would witness a change for the better.”

So, the wheel symbol is still actual in India, a rolling lasting millennia...

Giacomo Benedetti, Impruneta, Italy, 6/12/2016