Snapshot

Indian historian and archaeologist Ramachandran Nagaswamy was recently awarded the Padma Bhushan.

He is at the heart of that landmark case from back in the day, which involved the return of the Nagaraja idol back to India.

We revisit the case and Dr Nagaswamy’s contribution to its resolution.

https://swarajyamag.com/culture/the-nataraja-idol-case-illustrates-padma-bhushan-dr-nagaswamys-contribution-to-indian-heritage

History buffs across South India were ecstatic earlier this week – Dr Nagaswamy, the doyen of South Indian archaeology and history, was honoured with a Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian honour. The 87-year-old historian and scholar has had an illustrious history, including spending many decades with the Archaeological Survey of India. Nagaswamy founded the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department and served as its director for 22 years.

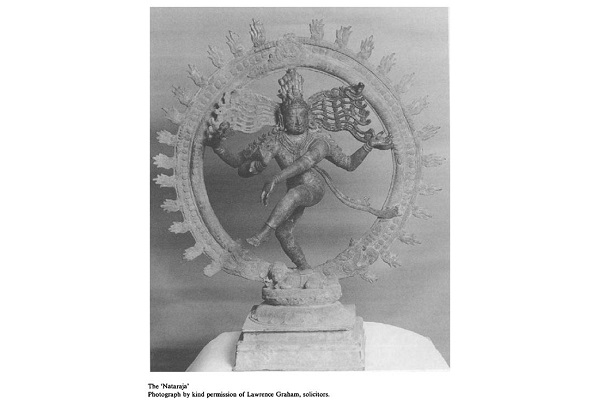

The recent Padma award to this history icon is a good excuse to revisit a historical case involving a large, exquisitely cast bronze Nataraja belonging to the Chola era, a Canada-based art collector and British courts. Nagaswamy was a key participant in the case, as you will see.

Sometime in 1976, Ramamoorthy, a labourer, was digging out the soil in Pathur, a village in the Kaveri delta district of Thiruvarur. As luck would have it, he discovered a stash of nine Chola bronzes buried on the site he was digging. Instead of reporting the case to the authorities, poor Ramamoorthy got in touch with some people and sold the largest among the idols, the Nataraja, to one Chandran for a measly sum of Rs 200. From there, the bronze appears to have found its way through the smuggling network to London, where it was handed to a London museum renovator to be readied for display in a Canadian museum.

The eventual buyer of the Pathur Nataraja was Bumper Development Corporation from Alberta, Canada. They had paid a princely sum of 250,000 British pounds to acquire the Nataraja from a London dealer called Sherrier, who had produced a false provenance paper for the idol. While the bronze idol was undergoing work, the British police impounded the idol on complaints of theft. It is believed that one of the smugglers who got a raw deal might have tipped off the police.

The British police were then issued a writ by Bumper Development Corporation, who claimed that they had legally acquired the idol. Indian authorities soon got involved and became plaintiffs in the case, saying the bronze was indeed smuggled illegally from India. Indian authorities too appeared to have been tipped off or acquired information as to the origins of Pathur Nataraja and had by now recovered the remaining idols from the stash that Ramamoorthy had discovered.

Among the Indian government’s arguments was to compare the sculptural styles and use the remaining eight bronzes to demonstrate the apparent similarity. All the eight recovered bronzes had been sent to London for the case hearings and along with them went one art historian well-versed in the field. The historian that Indian authorities had sent, was the Tamil Nadu state archaeology department director, and under whom some 25,000 metal images had been registered and studied. As you would have guessed by now, the historian was none other than Dr Nagaswamy.

Against Nagaswamy, Bumper Development Corporation fielded an art historian by the name of Gary Schwindler, then associate professor of art at Ohio University. He was well-known for his PhD dissertation on ‘The Dating Of South Indian Metal Sculptures’. Schwindler’s argument was that while the bronze in contention was indeed a Chola bronze, it was certainly not part of the Pathur group as they were quite different in style.

The judge in the case, Justice Ian Kennedy, now had the duty to study and decide the case on the basis of, among other things, the findings and opinions of the two art historians Nagaswamy and Schwindler.

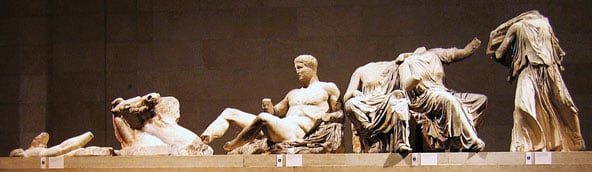

Schwindler suggested dating the bronzes by comparing the styles with stone sculptures found in temples. The temple sculptures were more accurately dated and if the styles in the Nataraja bronze matched certain temple sculptural styles, then one could reasonably assume the bronze belonged approximately to the same period as the temple.

Nagaswamy, it has been reported, suggested a “more comprehensive approach, using bronzes dated by inscription, bronzes dated by association with temples, comparisons between bronze and stone sculpture, and paleography to build an overall sense of stylistic sequence among Chola bronzes images”.

Three types of scientific fact were considered by the judge as ‘subsidiary evidence’. The first was metallurgical analysis. The plaintiffs wanted to show that both the Pathur Nataraja and the other eight recovered idols had the same metallurgical composition. But the analysis did not help as there was no “established chronological standard” of composition for bronzes.

Entomologists got into the act next, comparing termite runts on the bronzes. Indian authorities wanted to show that both the Nataraja and the other group of idols had similar black marks from termites running across the idols. Soil analysis of fragments still stuck to the bronzes was also tried and compared with the soil at the Pathur site, but this alone couldn’t help arrive at a conclusion as the burial process might have involved soil brought from outside, for example, from river sand.

The judge found Nagaswamy’s arguments persuasive and granted that the Nataraja bronze being contested over was originally from the Pathur temple. The case is even today cited as a great example of a cultural icon being returned to its original owners. The defendants went on to appealwhere they were dismissed; in fact, the Court of Appeal awarded the Pathur temple damages of some 1,000 British pounds. The plaintiffs were also awarded costs totalling around 300,000 pounds.

The Pathur Nataraja idol case remains a landmark even today for a number of legal precedents it set. It recognised the temple and the deity, Shiva, as a jurist entity which could sue or be sued. It caused quite a stir in the antiquities market – with the Pathur Nataraja case settled in the temple’s favour, any antique item stolen from a temple could now be claimed back citing this precedent.

The exquisite Pathur Nataraja, which had probably been buried during the Mohammedan invasions of South India, finally returned with much pomp to its former state of glory after many centuries. On 9 August 1991, the idol was handed over to then chief minister of Tamil Nadu Jayalalithaa. The idol was decked with flowers and pujas were conducted. A plan for renovating the Pathur temple was announced. Among those who received mementos from the chief minister on the occasion of the idol’s return was Dr Nagaswamy. His contribution to the case was widely regarded as critical and has been acknowledged so by many directly involved in the case.

Adrian Hamilton, Queen’s Counsel, London, in his written submission to the courts said, “Dr. Nagaswamy has brought to bear unequalled learning and experience in the historical, cultural, and religious aspects of the Chola Empire and the Hindu religion which flourished and which still flourish in Tamilnad and on the understanding of the inscriptions in the temples and on statues.”

The trial court judge made the following remarks: “..Dr. Nagaswamy, who I am satisfied, is an unequalled expert in his subject...Now considering the matter of style, again I prefer the evidence of Dr. Nagaswamy to that of Dr. Schwindler… I am satisfied that Nagaswamy is right in his summary taking the broader feel and treatment of the main points... I am satisfied that stylistic judgements in relation to Medieval Chola bronzes can not be more precisely determined than when Nagaswamy expressed his conclusions in his evidence.”

In the years thereafter, Nagaswamy would go on to accomplish much in his field. The Tamil Nadu government honoured him with a Kalaimamani award for his work on Periyapuranam, a notable Tamil work from the twelfth century. He brought back art performances into temples by organising the first Chidambaram Natyanjali festivals. That the union government has taken this long to recognise this unparalleled scholar is in fact a matter of shame. The Narendra Modi-led government deserves credit and applause for identifying and honouring scholars such as Nagaswamy.

It would be apt to close with a compliment that the Pathur Nataraja case trial judge, Kennedy, paid Dr Nagaswamy.

In the course of his observations, Kennedy had noted that Nagaswamy’s views put in front of the court were passionately held, and that he was a devout Hindu, and that it was easy to sense that Dr Nagaswamy was “deeply offended at the thought that idols of his Gods should be subject of commerce”.

What a wonderful thing it would be if everyone who had the power to protect and preserve India’s heritage could feel as offended about the current state of affairs as Nagaswamy had about Pathur Nataraja’s theft.

Post-script

The ruined Pathur temple was rebuilt but in a most tragic manner:

“The Tamil Nadu Archaeological Department has lined up and marked all the stones of the old temple for restoration. They had also excavated and found the remains of the temple wall that clearly showed the treasure had indeed been buried in the temple precincts. Only the bronzes were awaited. But soon after they arrived with great fanfare, everything on the site of the temple was bulldozed and a brick and mortar temple raised to house the deities!”

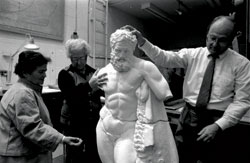

P. Chandra Sekharan with laser analyse

P. Chandra Sekharan with laser analyse

Identical looking idols with different chisel work on crowns: Minute differences

Identical looking idols with different chisel work on crowns: Minute differences