Indian cities have evolved over centuries, and in general do not have the grand layouts and leafy avenues of many of their more recent western counterparts. New Delhi is an exception, but then its layout is a western imposition and has nothing to do with the way old Delhi developed, or indeed any other city in India barring a few more recent exceptions.

Building codes

In every city, buildings are meant to conform to a set of building codes — informal earlier, now formalised. These codes are complex: buildings have to observe a minimum required front open space, possibly side and rear open spaces as well, with plinths often mandated to cover no more than a specified fraction of the plot area. The maximum number of floors is also often specified.

A post-World War II innovation from America introduced a new form of building control. This is called FSI (Floor Space Index) in India and FAR (Floor Area Ratio) everywhere else in the world. It is the ratio of built-up area of all floors on the plot to the area of the plot itself. The FSI regulation is welcomed by architects. They like the freedom to reduce the footprint of the building and increase the number of floors, while still observing the FSI rule which sets the total built-up area allowable on each particular plot. But from the authorities’ point of view, the FSI specified has to be carefully managed to ensure that the extent of built-up floor space permitted in a locality does not exceed that locality’s infrastructure capacity, in regard to water supply and sewerage of course but, more importantly, in regard to transport and crowding on the streets.

The World Bank has been relentlessly complaining that Indian cities are not optimally using their land. They particularly pick Mumbai to make this case and point out that the city’s irrational building rules impede good economic use of real estate. Alain Bertaud, in particular, a consultant to the World Bank, is vehement that FSI levels in Mumbai are too low and need to be immediately and drastically increased. Once this happens, it will become a model for the rest of the country. To underline its argument, the World Bank presents a bald comparison of FSI across international cities, which is both meaningless and misleading. It is like comparing individuals’ weights without considering their heights or the societies they live in. The policy recommendations that emerge can be both dangerous and damaging for the city.

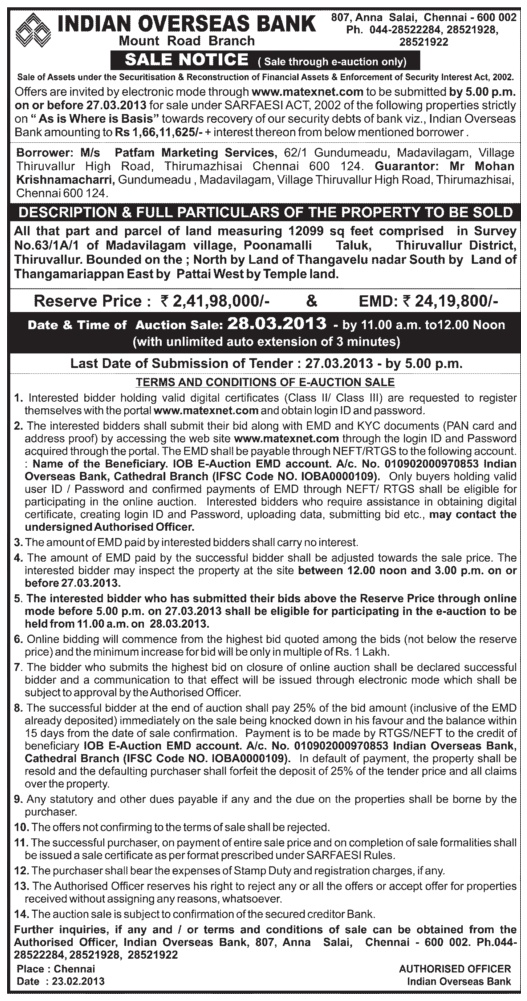

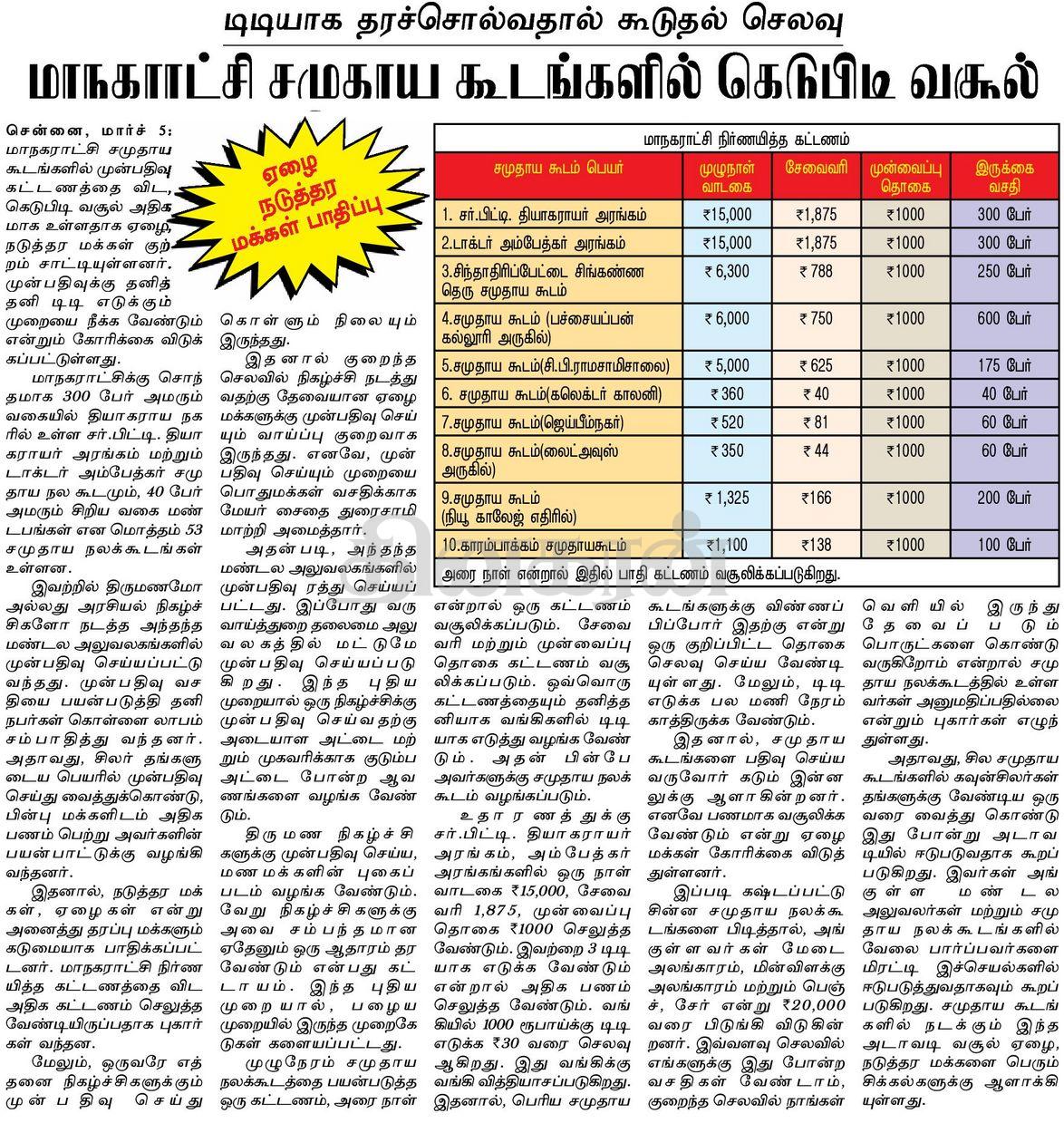

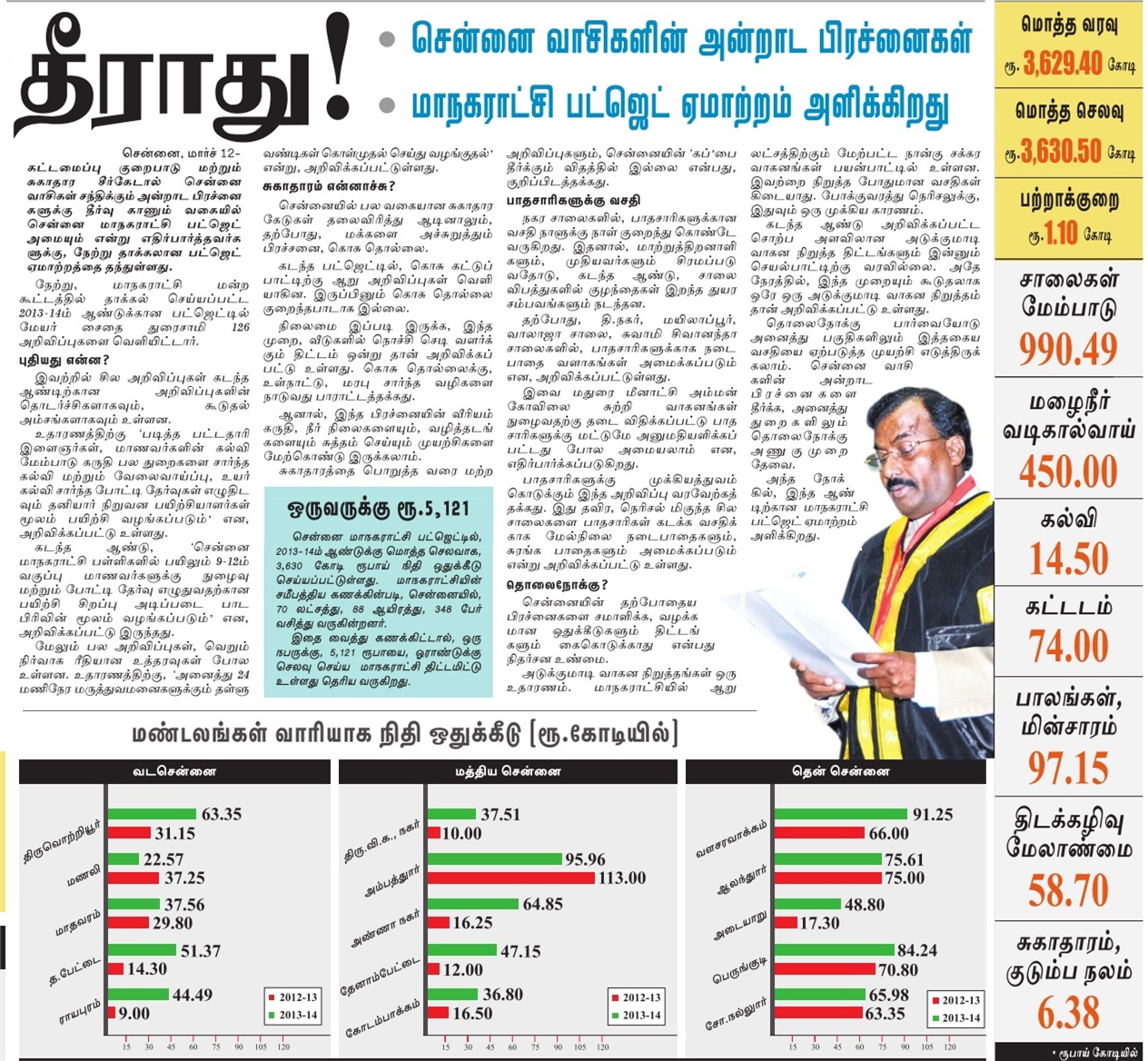

Here are the FSI values for one of the most crowded residential localities in Manhattan, Community District 8, known as the Upper East Side, compared with Mumbai’s C Ward, one of Mumbai’s densest areas:

On the strength of comparisons like this, Mumbai’s FSI has been portrayed as undesirably low and pushed up to 4, which is the current upper limit, except in the case of hotels, educational institutions, hospitals and the like where the limit can be much higher.

Indoor crowding

But there is a major factor missing in this World Bank’s comparison of FSI. This is that cities are at different levels of economic development, inhabited with individuals occupying, on average, different extents of floor space. Living is simply more crowded in some places, and less crowded in others. Here is a comparison of what we might call indoor crowding.

The following table highlights staggering differences: Manhattan, at 64 sq.m per person, has six times more residential floor space than someone in Mumbai’s C Ward, and Manhattan has over five times as much floor space per job. With such extravagant use, no wonder Manhattan needs a much larger FSI.

Buildable area

A second factor that is missing in comparing cities is the extent of buildable area: in other words, the proportion of buildable plots to street area. FSI applies only to buildable plots. In Manhattan’s CD-5 the Plot Factor (plot area / street area) is 1.7, which means 37 per cent of the area is under roads and only 65 per cent is available for construction (65/37 = 1.7). In Mumbai’s C Ward, the area under roads is less and the area available for construction is higher — 71 per cent buildable, 29 per cent streets (making for a Plot Factor of 2.4).

What must be factored into any debate on FSI is street crowding. This is an important index which gives an idea of how many occupants live within a given street area. It is the product of the number of residents per unit of floor area, the Plot Factor and FSI. Despite the higher FSI in Manhattan’s CD-8 (three times that of Mumbai’s C Ward), the street crowding is only 2,190 persons per hectare, whereas Mumbai’s C ward even with its lower FSI has 4,690 persons per hectare:

Mumbai’s C Ward already has its streets more than twice as crowded as Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Any doubling or quadrupling of FSI in Mumbai’s C Ward, as is being currently debated under prodding by the World Bank, will only double or quadruple its already massive street crowding to levels so far not seen anywhere in the world.

We have recently witnessed this in a small way in Mumbai’s suburbs. In October 1997, there was a sudden relaxation and FSI could be increased from 1 to 2 in the western suburbs, using Transferable Development Rights. Everyone experienced the sudden increase in traffic volumes, a new and infuriating congestion arising from a doubling of traffic which could not be explained by the slow rise in car ownership, and was much more closely related to the increase in building volumes.

The World Bank’s comparison of international FSI values is thus simplistic in the extreme and seriously misleading, because it ignores the other equally relevant parameters of indoor crowding and Plot Factor. Pressing for a major upward revision of FSI without a corresponding improvement in infrastructure, particularly transport to deal with crowding, is logically indefensible. It promises something it cannot deliver, an improvement in the quality of life. For the poor, and the vast majority of citizens, it will result in a worsening of living conditions, particularly travelling conditions. But worst of all, it is a red herring. It distracts us from the central problem, which is that adding to the city’s land area by establishing new transport arteries is being invariably and unaccountably delayed. There is also a deliberate companion policy of withholding land from the market by one means or another. How to keep land in short supply is thus the name of the game, by which fortunes can be made in short order, and never mind what happens to Mumbai or its citizens.

(Shirish B. Patel is a civil engineer by training and an Urban Planner by accident, experience and inclination. He was one of the three original authors of the idea of New Bombay, and for its first five years was in charge of planning, design and execution for the new city.)

Doubling or quadrupling Mumbai’s FSI will only increase its massive street crowding